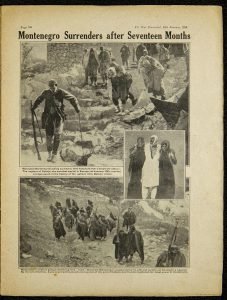

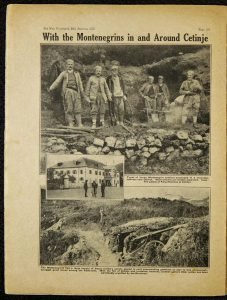

Like our first workshop (see the round up here: https://normmanetwork.com/first-digitizing-the-war-illustrated-workshop-roundup/) the second also covered an eclectic array of subjects including: locations, espionage, the use of language, nursing, zeppelins and films and stars. Some of these subjects provided a link to our first workshop as locations were again a popular choice. One of our participants researched their Kentish hometown. Another attendee searched for coverage about the country Montenegro. The way Montenegro’s surrender was reported was thought to be especially interesting. In the 29th of January 1916 issue of The War Illustrated the page ‘With the Montenegrins in and Around Cetinje’ (p. 558) appeared. Photographs show the mountainous region and the ‘hardy’ mostly ‘middle-aged men’ trying to defend it. Only after this, and a picture of King Nicholas’ palace, does a caption to soldiers with heavy artillery reveal that both Cetinje and Lovtchen have fallen. The bravery of the people of Montenegro is emphasised, though, as in addition to noting that their weapons were in ‘commanding positions’ and ‘wrought great havoc among the Austrians’ it is described as a ‘gallant little nation’. On the opposite page the headline is unequivocal: ‘Montenegro Surrenders after Seventeen Months’ (p. 559). The opinion that Montenegro is ‘gallant’ is repeated, but unlike the preceding page, most of the pictures now show wounded soldiers being aided by others. It was commented on that elsewhere in the archive the women of Montenegro were presented as carrying out physical work (road-building) – both genders made significant contributions. Interestingly, the editor attempted to bring the magnitude of what happened, and the surprising way Montenegro held out, by comparing the size of the population of the whole country (250,000) to that of a large town in Britain – Nottingham.

Espionage was once more a topic of interest. Rather than focusing on individuals (such as Mata Hari as noted in the last roundup) someone took a broader approach by searching terms like ‘espionage’, spy’, ‘spies’ etc. This brought up national and gender differences. The British would of course not engage in such deceptive practices (it would not be cricket), while it was thought unsurprising that women were capable of duplicity. A drawing entitled ‘Woman spy guards secret German telephone’ (2nd January 1915 p. 476) shows a woman in an unusually active pose – her hands are around a soldier’s neck. Significantly this is not a woman connected to the Allies, but one apparently working for the Germans. The woman did not initially hoodwink the French soldiers by her sexuality. Instead she played on the vulnerability of her gender as she ‘tearfully complained that the Germans had ransacked the place, leaving her destitute’. Only the fact that the French soldiers insisted on searching the farmhouse revealed a German hiding in a barrel in the cellar, meaning that the women ‘sprang upon a French soldier and tried to throttle him’. Even non-humans were involved in spying. The whole group was interested to hear about spy dogs which were sent ahead of soldiers to see if the opposition’s trenches were occupied.

An interest in language flagged up in the first workshop was continued in the second. The use of emotive language was more akin to that seen in novels rather than objective reporting. Indeed, some well-known novelists (including Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle) wrote articles for the magazine. Specific words used to describe the war were also searched for. It was found that ‘terror’ and ‘horror’, words we retrospectively attach to the conflict, were not present until later issues of the magazine. We thought this was likely to be connected to the fact that at the war’s beginning it was not anticipated that it would necessarily last for long. As time progressed, the public needed to be galvanised to support the cause and striking language helped to achieve this.

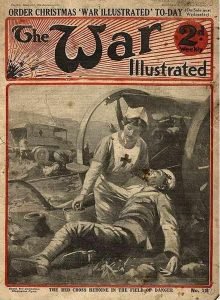

A new topic, but one which came up in our workshops at the Beaney in 2017, was the magazine’s view of nursing. To start with, references were largely patronising – only considering that women could take on a nursing role in order to prepare them for being wives and mothers. It was only in 1918 that a series of articles by nurse Olive Dent began to appear. As with the shift in language to use terms like ‘terror’ and ‘horror’ as time went on, it became clear that nurses were essential to the war effort and should be respected as such.

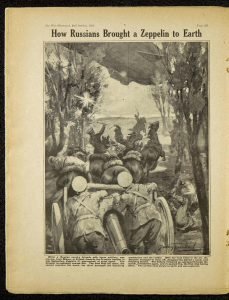

In contrast to those trying to heal and provide succour to the wounded, another focus was the zeppelin, Germany’s most iconic weapon of the first world war. The use of airships was portrayed as especially reprehensible, as ‘The Death Harvest of the Dastard Zeppelin’ makes clear (26th Sept 1914, p. ii). Unlike earlier wars which were largely fought on the battlefield, zeppelins also put civilians at risk, as they killed people indiscriminately. At this point it was thought that Britain should not follow suit. Later on, however, the argument that since the Germans had started using such weapons Britain would be justified by also doing so, was proposed.

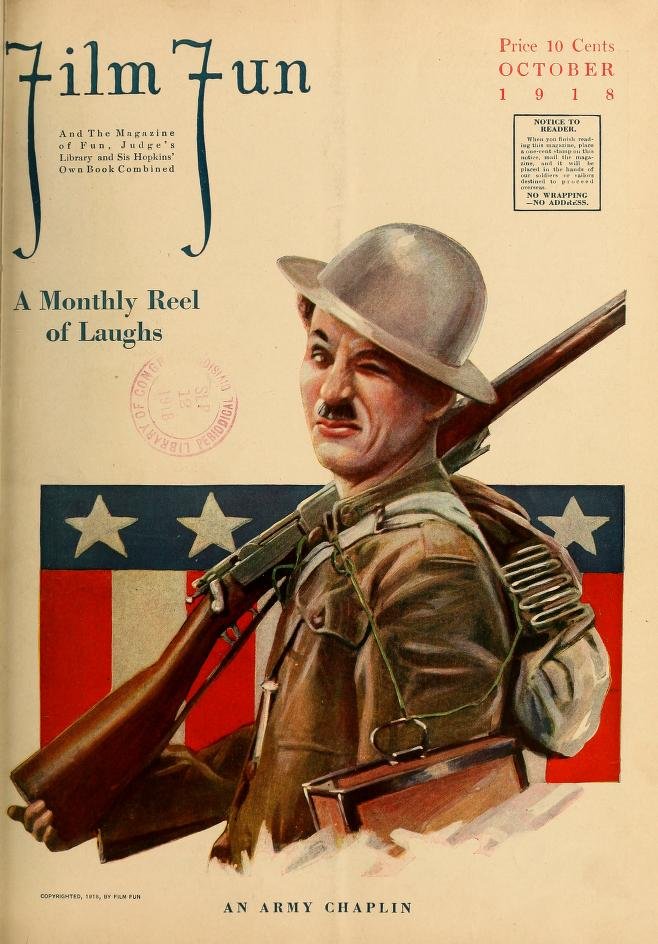

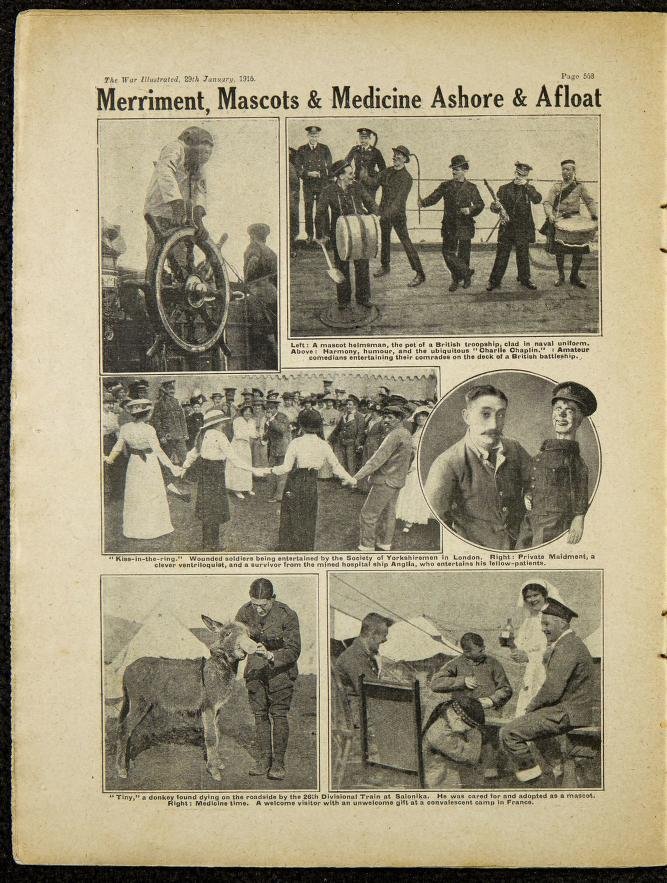

Because members of NoRMMA are also interested in film, this rea was also researched. Searching for specific terms like ‘film’ brought up some interesting ways in which this was primarily related to photography and conceptualised as ‘fragments’. We also looked at some stars. The biggest American star of the day, Mary Pickford, did not appear. Pickford’s fellow Hollywood star Charles Chaplin had a British background and was present in the magazine, however. On a page titled ‘Merriment, Mascots & Medicine Ashore and Afloat’ (29th January 1916, page 568) several photographs and captions appear. The second photograph pictures several men in costume standing in front of naval officer. This is accompanied by the caption: ‘harmony, humour, and the ubiquitous “Charlie Chaplin”: Amateur comedians entertaining their comrades on the deck of a British battleship’. The trope of soldiers entertaining one another prompted discussion about World War II films in which this often occurred. For example, in The Colditz Story (1955) Ian Carmichael and Richard Wattis performed routines by music hall comedians Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen. We discussed whether other music hall stars might also appear in the magazines, and if this was more likely than film stars being present. While Chaplin is only mentioned once, the fact that he is described as ‘ubiquitous’ points to his wide popularity. (This is also seen in some US fan magazines of the time which show him in uniform.) Such mentions of world war I in fan magazines was thought to be another interesting route explore.