Today, our blog features a guest post by Oana-Maria Mazilu (University of Kent), one of our conference presenters who is currently working on her PhD on Romanian movie magazine culture.

Hello NoRMMAs,

Following my presentation on Nicolae Ceausescu’s image in the Romanian film magazine Cinema for our Ghent conference, I thought I would take this opportunity to show and discuss the fun period of the magazine: the Monarchy period or the years 1924 to 1948. Just to make things clear, I think it is important to briefly discuss Cinema‘s publication period and what makes it such a fascinating magazine.

Cinema presents three publication times: I. 1924-1948, II. 1963-1989 and finally III. 1989-1998.

Cinema cover, Nr. 536, 1941

Noul Cinema cover, Issue 2, 1991

Interestingly, the publishing periods coincide with major political change in the country; the fall of Monarchy and the advent of Communism and the relaunch of the magazine as Noul Cinema (the New Cinema) in the spirit of the 1989 revolution and also marking the shift to capitalist democracy.

Unlike the Communist period which was marked by aggressive propaganda, the personality cult of the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and a focus on Romanian film, the 1924-1948 Cinema presents its readers with all the glitz, gossip and glam of Hollywood.

My research suggests that during this time, the magazine was a weekly publication under the editor G. Ionescu with the director of the magazine T. Teodorescu-Braniste. I should mention that so far, I have only looked at issues from 1937, 1939, 1940 and 1941. Unfortunately, the issues of this period are rare and hard to find. There is no complete collection available in libraries and digitalisation and online availability are still a long way away. Thus, certain details are liable to change or some of them may not be valid for the entire 1924- 1948 period. However, one thing is certain: the fascination for Hollywood stars and films and the approach to these elements ultimately mark the Cinema of this period as a fan magazine.

Evidence of this lies in glamorous covers and the discourse set by sections and articles. Here are some articles and photos which caught my eye and some surface observations.

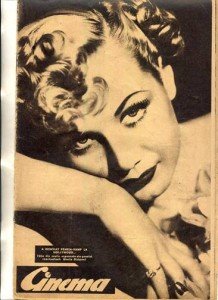

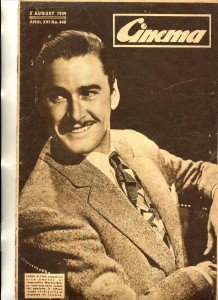

Gloria Dickson on the cover of Cinema, No. 468, 1940

Errol Flynn on the cover of Cinema No. 440, 1939

Such photos are also present in the inside of the magazine pages.

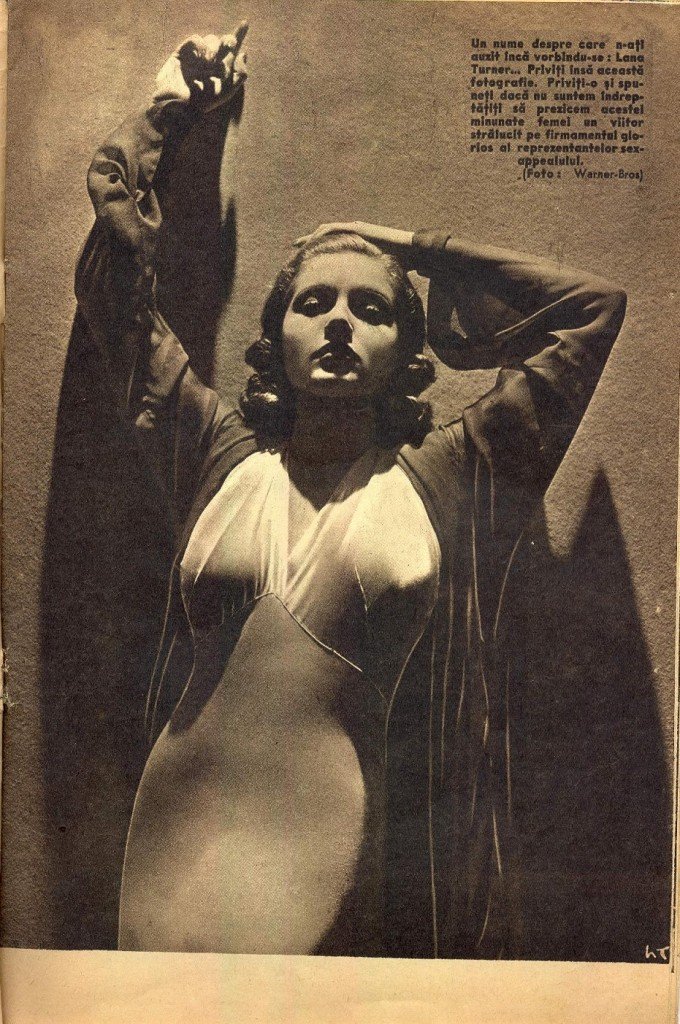

Lana Turner, Cinema, No 355, 1937

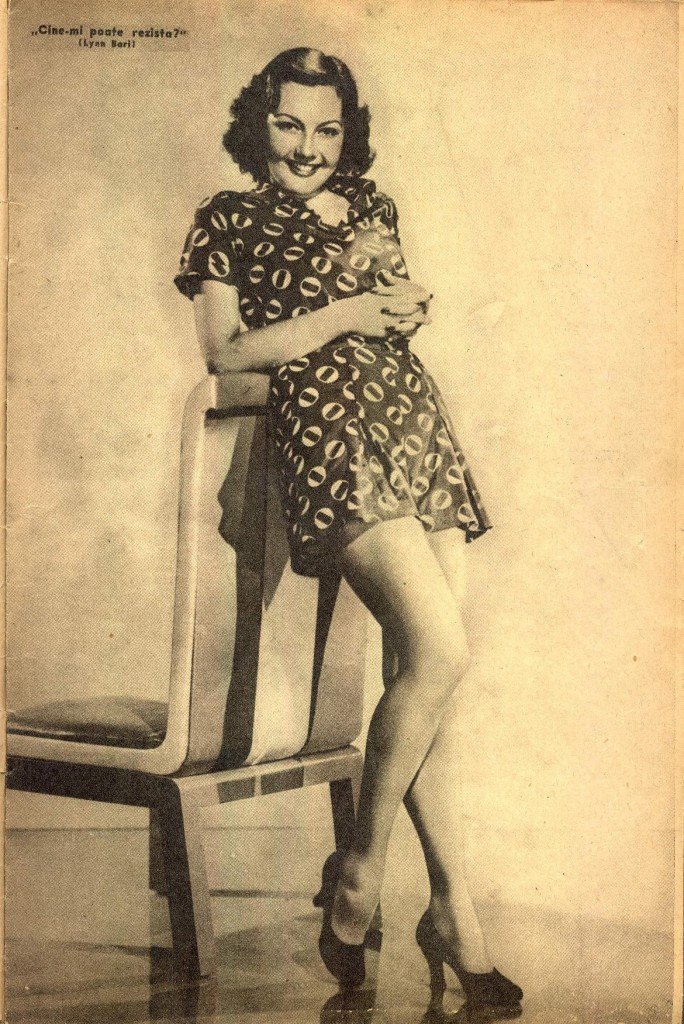

Lynn Bari in Cinema, No. 342, 1937

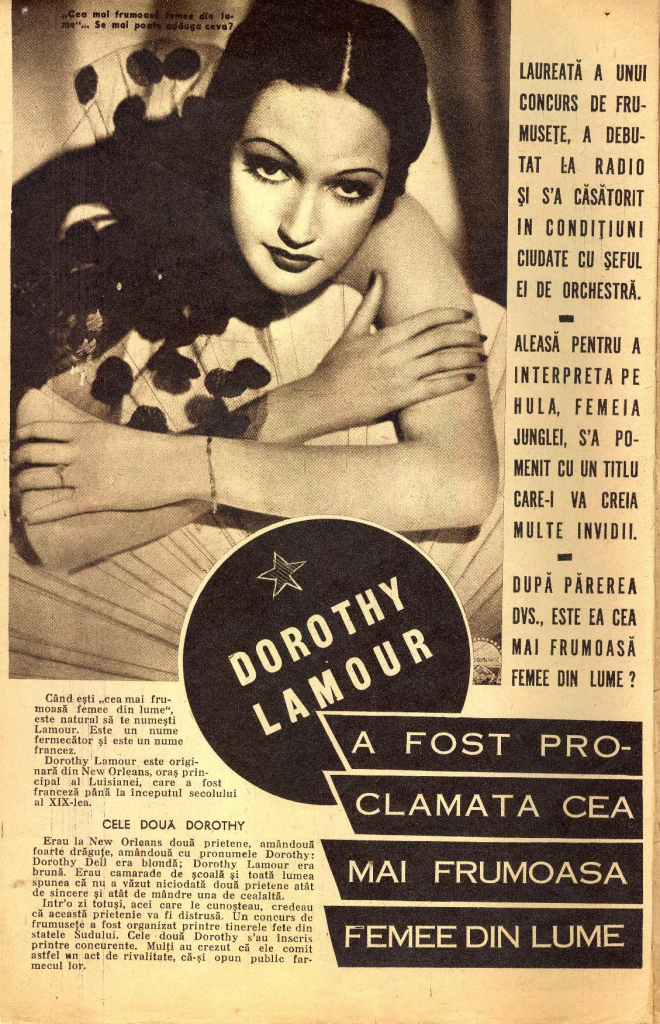

The emphasis on beauty is also present in articles and it is naturally discussed in relation to stars.

Dorothy Lamour is declared the most beautiful woman in the world.

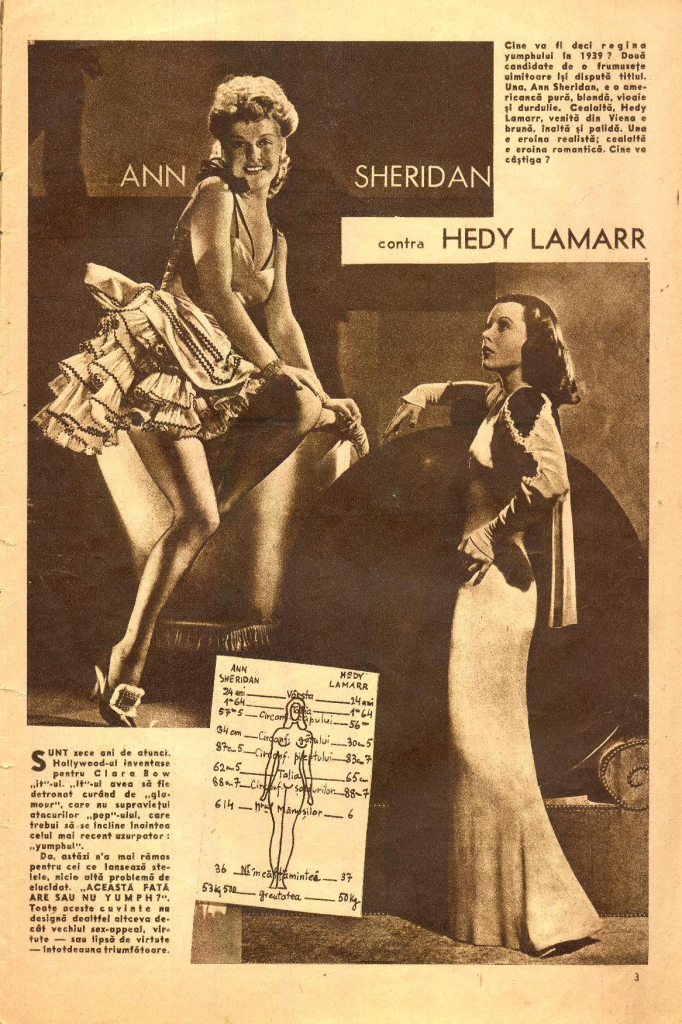

And of course, a standard of beauty must be established. Notice in this article ‘Ann Sheridan against Hedy Lamarr’ how the two stars are placed in competition based on their physical appearance. How striking is that diagram of the female body?!

However, not only female stars are held to a certain beauty standard. Male stars were also susceptible to this perspective as suggested by the article ‘Not only actresses, but also actors pay a heavy price for their beauty’. Just to offer a couple of examples from the article, apparently Robert Taylor plucked his hair to maintain that gorgeous hairline while Clark Gable had a rigorous workout to maintain his figure.

Cinema of this time would not be a fan magazine without gossip and insight into the personal lives of stars.

‘Hollywood always Hollywood- Latest Gossip’, Cinema, No. 342, 1937 p.17

‘Hollywood always Hollywood- Latest Gossip’, Cinema, No. 342, 1937 p.17

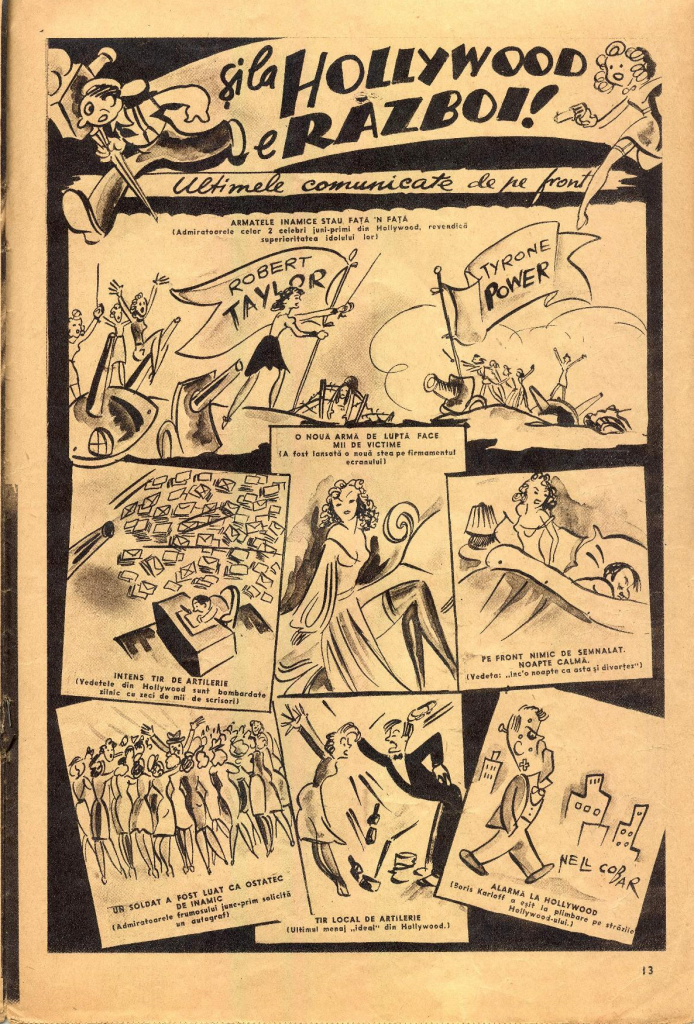

Sketches- ‘Hollywood is at war too!’, Cinema, No. 468, 1940, p.13

‘Why they can’t stand each other: Joan Crawford- Norma Shearer, Dorothy Lamour-Patricia Marison, Bette Davis-Miriam Hopkins ‘- Cinema, No 539, 1941, p.3-4

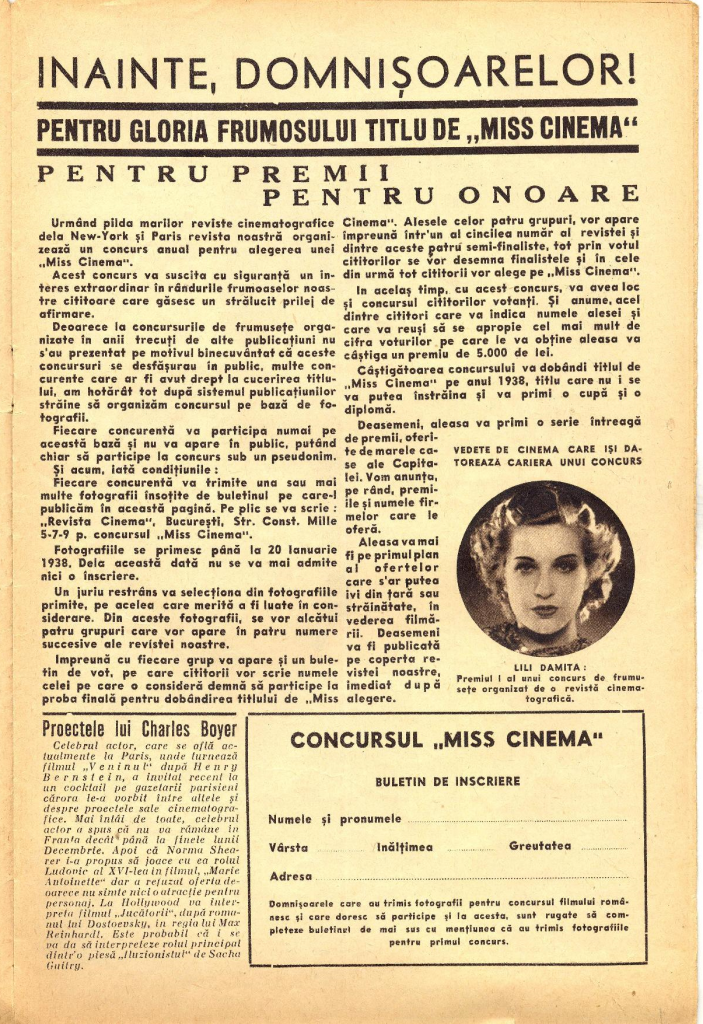

And why shouldn’t female readers get in on all this beauty, glamour and stardom?! Send your photo and complete the form with your details (don’t forget your height and weight) for a chance to become Miss Cinema!

‘Forward Ladies! For the glory of the famous title of Miss Cinema.’ Cinema, No. 353, 1937

The relationship between the magazine and its readers is also established through letters and responses. Readers are invited to write to Popeye in the regular section ‘Let’s talk’. The magazine only publishes Popeye’s responses and, as in the case of Hollywood fan magazines, there is a question in regards to the authenticity of these letters. Readers write using false names such as ‘T.D. Loco’, ‘The queen of the night’, ‘The Romanian Errol Flynn’ or in this example, ‘Conchita’, ‘Babydoll’ or ‘Pierre’. Popeye replies with humour and sarcasm to readers, making for a both entertaining and informative section.

To conclude, Cinema of the years 1924-1948 is close to the fan magazine model from Hollywood. The focus on stars, the gossip columns, the emphasis on beauty and glamour, the contest and the responses to fans make this period of the magazine very different to its Communist successor… and much more fun research material.